Rolling Open

Circles, spirals, and how intersecting cycles help us hold open the portals between heaven and earth.

A couple of years back, a local Unitarian Universalist community asked me to come teach them about the holiday of Sukkot. I was happy to oblige, and standing in their breezy pop-up sukkah eagerly shared an insight I had recently had: that the autumnal Jewish holy day cycle follows the classic pattern of initiation rites found worldwide. In this acknowledged sequence, the candidate is first prepared for the coming transformation. Next comes the test itself. And finally, the initiate returns to society, where their new status is recognized and celebrated in community.

Beginning a new Jewish year follows this same pattern. At Rosh HaShanah we prepare by blowing the shofar, a wake-up call alerting us that the great books of life and death are open before the Holy One. On Yom Kippur, we undertake the ordeal itself, fasting and restricting ourselves in a ritual rehearsal for death. It is a trial we hope to come through lightened, maybe even a little enlightened, awash with a sense of forgiveness and the possibility of a fresh page in the book of life.

The final stage, acknowledging the space traversed and celebrating our survival, is Sukkot. By constructing a fragile booth, a distinctive semi-outdoor environment in which we gather for seven days, we literally create a container in which to integrate and affirm the initiation we have undergone.

As I finished my exposition, a bright-eyed (presumably Jewish / U-Jew) older gentleman in the group chimed in and said, “Yes! All so we can read the Torah again as new beings!”

For, as my interlocutor so rightly observed, as we reach the end of the high holy day cycle, we roll right into a new beginning - the beginning from the beginning (again) of reading the Torah, its famous opening words (“In a beginning”) explaining how the world we know came to be.

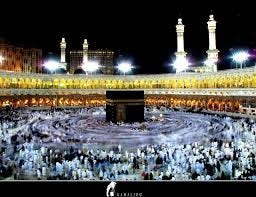

Interestingly, as these two cycles - of the holy days, and of the communal reading of the Torah - intersect, we celebrate them through literally moving in circles. Throughout the festival of Sukkot, traditional communities practiced hakafot, literally ‘circuits’, in which participants circumambulate the sanctuary with their special four-species plant bundles, while the Torah scrolls are held as linchpins in the middle of the room.

As the holiday reaches its peak, on Hoshanah Rabbah (the final day of Sukkot proper) this is amplified into a half-day of prayers, in which seven sets of circumambulations take center stage. Then, as we transition directly into Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, the very last days of the holiday cycle, we continue with yet more circuits - this time (twice) making seven sets of dances around the sanctuary, once by night and again the next day. For these we dance with the Torah scrolls in our arms, celebrating reaching the story’s end – only to begin it again.

As a professional ritualist, I’m wont to take note of things like which direction people go in when they make these circuits, and it struck me as curious that the standard is to go counter-clockwise, a direction your pagan friends might call ‘widdershins.’ In non-Jewish ritual, clockwise or ‘sunwise’ is generally preferred, and like taking the lid off a jam jar, clockwise usually represents opening while counter-clockwise means closing. So why do we go this way round?

My suggestion is that in synagogues we intuitively move counter-clockwise because this echoes the way the scroll of the Torah is physically rolled as we read it. Since Hebrew is written right to left and the Torah scroll is constructed of parchment wound onto two wooden rollers, the motion of its winding, as we move from start to end, is widdershins. Thus our counter-clockwise dances I think less represent closure and culmination (though maybe you could make a case for that) than they do a movement to open, or keep open, the portals between the heavenly realms and this one. Because the heavens’ opening - as we shall see - is very much part of the days’ work.

Before I say more about that I want first to say more about circles, and note that the word hakafah, circuit, is echoed in the very name applied to this portion of the year. In some of the oldest instructions for celebrating a festival calendar, the time we now call Sukkot is designated ‘at the turning of the year’ (Exodus 34) - in Hebrew, tekufat ha’shanah. The word tekufah, turning, and hakafah, circuit, share a root. What is more, another very ancient name for Sukkot is simply ‘the Holiday’ (see Mishna Rosh HaShanah 1:2) - or in Hebrew, the Chag. The word chag, like its Arabic cognate hajj, actually also implies a circuit, being connected both to the word for dancing in circles, and to the word for making pilgrimage - a circular route. We evidently still celebrate with the spiritual technology of circle-dances, and although we no longer formally practice pilgrimage, it’s possible that our circuitous movements around the prayer space in some way evoke this sacred there and back again.

Sukkot is also a time to dwell on life’s cyclicality, in particular through its seasonal invitation to study the book of Kohelet. One of the Bible’s great wisdom texts, Kohelet / Ecclesiastes’ philosophical musings center on transience, change, predictability, and, as the Byrds made famous, there being a time for every purpose under heaven: a time to be born, a time to die, a time to reap and a time to sow - along with various other such pairs suggesting the cyclical, repetitive nature of living.

As we read about life’s circularity, and celebrate through collectively enacting circular form, another literal heaven-and-earth circuit comes dramatically into focus: the water cycle.

Because as I mentioned before, it is exactly at this point of interconnection, as we use our hakafot to ‘turn the wheel of the year,’ that we ask the All-Being to open the heavens, “return the winds and send down the rains.” This refrain, which becomes a thrice-daily liturgical addition throughout the winter months, is added with great focal ceremony and a special one-off set of texts on Shemini Atzeret, right in the midst of this three days of major circling.

Shemini Atzeret, literally “an Eighth of Assembly,” or “an Eighth of Stopping” is a bit of a mysterious holiday, a final holding out for the sacred season not yet to end. The rabbis famously explain this as a sort of divine after-party with the chosen people. Whereas Sukkot makes moves to universalism, with 70 bulls being offered on behalf of the 70 nations of earth, the sacrificial menu for Shemini Atzeret is a great deal more modest, as if God is saying to us: “Don’t go home yet. Stay another day and let’s just have some time together.” Fascinatingly, in one midrashic version of this idea (Tanchuma, Pinchas 16), the word God uses in this invitation is me’galgel. In context it seems to mean something like ‘make do’ (with the limited menu), but galgal, like our presumably related English word ‘wheel,’ literally means to turn or roll around. Whether God is asking us to slow the roll and hang out for a bit, or to make moves to help turn things around, the image is again one of rotation.

A final intersection in this Venn diagram of festivity can be found with a little focus on linguistics. As those familiar with the text of the Shema might remember, the Hebrew word for early (or autumnal) rains is yoreh. (Malkosh, by contrast, denotes the rains of spring). What is the etymology of yoreh? Well (perhaps also related to our English word ‘arrow’), it has to do with something traveling from point A to point B. And to what other well-known Hebrew word does yoreh relate? That other mysterious transmission from somewhere else to here: Torah. That’s right — divine teaching is directly related to rain. Both give indispensable life and nourishment from beyond; and both rest on repetition, but take us somewhere new.

Now that we have reached the end of the holidays and turned the Torah back to column one, we do actually manage to move on a little: into a new month, Cheshvan.

As the eighth month* in a system that sacralizes sevens, Cheshvan implies the possibility of going back to the beginning, like a circle - or, with the addition of a certain directionality, creating not a circle but instead a spiral. As we march in circuits, dance in circles, and engage one another in turning the wheel of the year, we ask for continuity, for survival – but we also ask more than that. We ask for transmission, for direction, for the addition of new teaching (Torah), new life (rain) – for something that comes from beyond, helps us grow, moves us forward and helps us get where we’re going.

Now that we’re here, in Cheshvan, this journey really gets under way. May we see where we’re headed, and may our circle spiral onwards with new life, new rain and new, inspiring Torah. I am wishing you a chodesh tov - may it be a good month.

*Yes, the new year / Rosh HaShanah occurs in the seventh month! And one way of understanding that is that like a foetus, the year is made not top-down but rather middle-outwards — so here we are in yet another circle, the sacred belly-button of time. It’s a navel worth gazing at.